My chapter, “The Unicorn as a Symbol for Christ in Medieval Culture,” is now forthcoming in Illuminating Jesus in the Middle Ages, ed. Jane Beal (Leiden: Brill, 2019).

Analysis of “The Lady and the Unicorn” Tapestries

The images in the six tapestries called The Lady and the Unicorn (or La dame et licorne) participate in network of inter-connected meanings or, perhaps, in four levels of meaning. The imagery includes sacred (allegorical) and secular (literal or historical) senses in the service of the artistic representation of late-medieval Catholic virtue among the nobility. This is certainly tied to the patrons of the tapestries, the Le Viste family of Lyon, France.

The Le Viste family arms are represented in each of the tapestries, indicating their patronage of these extraordinary works of art. Scholarly consensus originally held that Jean IV Le Viste commissioned them, which makes sense because he was in possession of at least three sets of large tapestries, apparently including The Lady and the Unicorn, that are mentioned in his will and were given upon his death to the eldest of his three daughters, Claude. However, there is another argument attributing patronage to Antoine Le Viste, cousin germain of Jean IV Le Viste, perhaps in honor of his affianced, Jacquelin Raguier, whom he married in 1515. (1) Scholars have long doubted that these are wedding tapestries, however, because if they were, by tradition, they would represent the coats of arms of the families of both bride and groom: these six tapestries represent only the Le Viste family arms, and so it is unlikely that The Lady and the Unicorn tapestries were made to honor a nuptial celebration.

Since 1921, when A.F. Kendrick identified the tapestries as having been made in the medieval tradition of the “allegory of the senses,” modern viewers have been taught to read five of the tapestries as representative of sight, hearing, smell, taste, touch:

- Sight: The Lady holds a mirror up to the Unicorn.

- Hearing: The Lady plays the harmonium.

- Smell: The Lady makes a chaplet of flowers while a nearby monkey sniffs a flower.

- Taste: The Lady apparently gives a small, round, white sweet to a bird (which the bird holds in one claw while the other rests on her left hand).

- Touch: The Lady grasps the horn of the unicorn.

The sixth tapestry, which admittedly does not fit well with this scheme, may represent a sixth idea, such as the will (“a mon seul desir”) (2), or, enigmatically, relinquishment (because the lady is placing her necklace in a casket – unless, of course, she is actually taking the necklace out of the casket).

Source: Wikipedia

Source: Wikipedia

Two other different but nevertheless cogent interpretations of the The Lady and the Unicorn have been put forward in recent years.

In 1997, Kristina Gourlay argued the The Lady and the Unicorn tapestry series is not so much an “allegory of the senses” as it is a representation of the “iconography of love.” Looking to Richard de Fournival’s thirteenth-century Bestiare d’Amour, which contains a chivalric version of the mystical hunt of the unicorn story, she focuses on the tapestry that depicts the lady with the unicorn in her lap and develops an argument re-interpreting The Lady and the Unicorn as a story about the progress of a romance. In her scheme:

- Taste becomes the initial “pursuit”: this is symbolized by the bird, read as a hawk, who represents her lover and the hunt of love motif; the small, round, white object she gives to the bird is not a sweet, but a pearl (which may represent the soul).

- Hearing becomes “harmony” in the romantic relationship;

- Smell becomes “recognition,” for she is weaving the chaplet of flowers for her lover as a token of her returned affection.

- Sight becomes “capitulation,” symbolized by the unicorn in her lap;

- Touch becomes “capture” when the Lady holds the unicorn’s horn in her hand and the myriad smaller animals in the tapestry are all depicted as collared.

- Finally, A mon seul desir, difficult to explain with the allegory of the five senses, becomes “resolution”: to symbolize marriage, the Lady lays aside her own “device,” her necklace, in preparation to take up her husband’s arms. (3)

In 2000, Marie-Elisabeth Bruel read the tapestries in terms of noble virtues portrayed as allegorical female figures in the Roman de la Rose, equating “sight” with Oiseuse (idleness), “touch” with Richesse (wealth), “taste” with Franchise (candor or freedom of the spirit), “hearing” with Liesse (joy), “smell” with Beauté (beauty), and “a mon seul desir” with Largesse (generosity). (4) Bruel’s model, reading The Lady and the Unicorn in terms of an influential medieval literary work, has been followed by others who have read the tapestries in light of the works of Jean Gerson and Christine de Pizan. (5)

According to these three major interpretations of the series as whole, as well as related studies, the Lady may represent the soul (anima) and the soul’s responses to the senses. She may represent the ideal woman, either in her virtue or her desirability as a lover (or both). She may be inspired, to some degree, by well-known medieval literary works. Furthermore, she may be intended to glorify the nobility of the Le Viste family, woo a spouse into the Le Viste family, educate the daughters of the Le Viste family in the virtues they should possess or advertise the marriageability of the young women in the Le Viste family.

Recently, in her a careful heraldric study of the tapestries, Carmen Decu Teodorescu has suggested that the particular coats of arms represented in the tapestries belonged to Antoine Le Viste, not to Jean IV Le Viste. (6) First noticed by Marice Dayras in 1963, the changes made to the Le Viste family arms in the tapestries were hypothesized by Carmen Decu Teodorescu in 2010 to be a “mark of cadency.” Such a mark is “used in heraldry to indicate by its addition to an armorial the birth order of a male heir. The cadency mark has been traditionally used to differentiate between different branches of a family which bear the same arms.” (7) As has been observed, “Cette hypothèse est renforcée par le fait que son blazon se trouve sur la rose méridionale de l’église Saint-Germain-l’Auxerrois de Paris qui a été commandé par Antoine Le Viste par un marché passé en 1532.” (8)

Source: Wikipedia

There are four distinguishing differences in this series of six tapestries: the differences are between banners, the lady’s hair length, the presence or absence of an additional woman, and the wearing of shields (or capes) by the lion and the unicorn.

- Four of the six tapestries contain two banners, one square and one rectangular but split on one end into two curling scrolls, while two contain only the square banner.

- The Lady in the two tapestries with the single square banner has the long hair while the Lady of the four tapestries with the two banners has shoulder-length hair. The Lady of the four tapestries sits or stands alone between the lion and the unicorn.

- However, in the four tapestries with two banners, a second woman of shorter stature appears with the central Lady in all four cases.

- Interestingly, in one of the two tapestries with one banner and a long-haired, solitary Lady, the lion and the unicorn wear shields. In one of the four tapestries with two banners and a tall, short-haired Lady with a shorter woman near her, the lion and the unicorn wear shields, but ones different in shape from those in the two tapestries with a solitary Lady. In another of the four tapestries, the lion and the unicorn wear emblazoned capes.

Based on these major, easily visible distinguishing differences, quite possibly there are at least two different Le Viste tapestry sets here that have been combined, received, and interpreted as a single set. There may have been additional tapestries, now lost, in either set. This idea is not new, but it is significant for interpretation of meaning.

The idea that the central lady in the tapestries represents the Virgin Mary certainly has been considered, but it is not now widely accepted. This is in part because the connection with Mary is not as explicit in The Lady and the Unicorn as in other representations, like the 1480 Swiss tapestry altar frontal (discussed above), though it should be noted that some representations of the Virgin are quite simple, without halo or many identifying symbols around her. By contrast, the prominently displayed Le Viste family arms are quite explicitly and repeatedly displayed, leading art historians to investigate the historical situatedness of the works in terms of their patronage.

Yet culturally literate medieval people were accustomed to understanding the stories, visual art, and architecture around them at multiple levels of meaning: literally and allegorically. It is likely that The Lady and the Unicorn participates in such a network of meaning. Literally and historically, the tapestries may pertain to the women of Le Viste family: their virtue, beauty, and desirability. At the same time, allegorically or spiritually, the tapestries can be characterized as Marian, if not exclusively about Mary, and Christian, if not exclusively about Christ. The Lady is like Mary because the women of the Le Viste family seek to emulate the Virgin. Both the unicorn and the lion are like Jesus because the chivalric male head of their household seeks to emulate Christ. (9) Morally, the tapestries encourage multiple meditative practices, common to late-medieval lay Catholic spirituality, intended to edify the viewers with respect to guarding their senses, and thus, their souls, since the senses are gateways to the soul. Anagogically, they may represent matters unfolding in the future, including the laying aside of wealth in order to receive a heavenly crown.

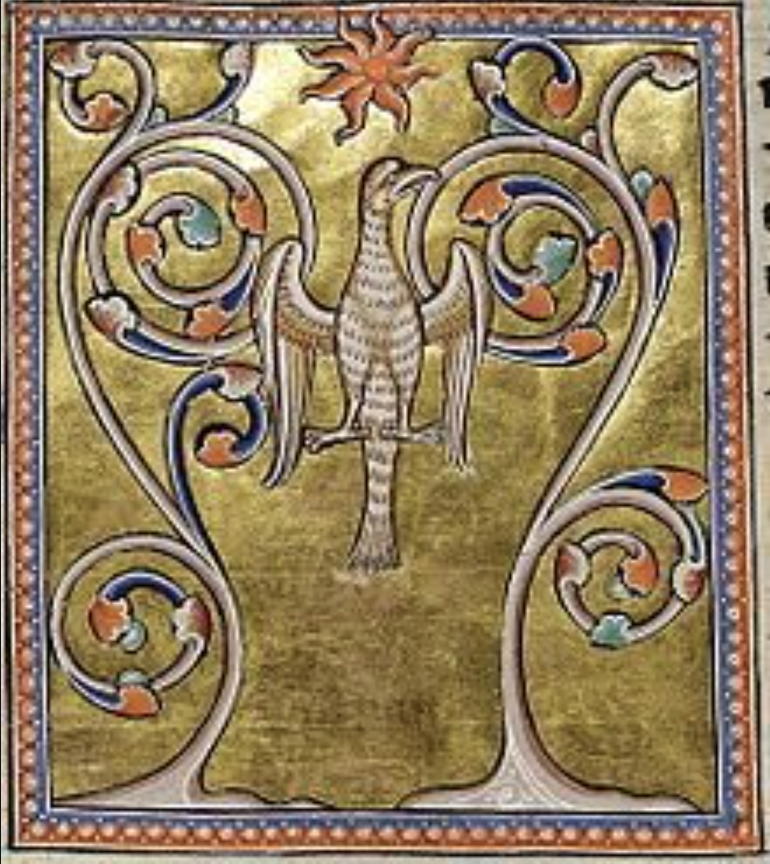

One image in the series particularly evokes the idea of the virgin capture of the unicorn: the tapestry most commonly called “Sight.”

Source: Wikipedia

Source: Wikipedia

Author’s note: For further analysis of the tapestries in the context of Christian unicorn symbolism in the Middle Ages, please see my chapter, “The Unicorn as a Symbol for Christ in Medieval Culture,” in Illuminating Jesus in the Middle Ages, ed. Jane Beal (Leiden: Brill, forthcoming).

Works Cited

1. Sophie Schneelbalg-Perelman, “La Dame à la licorne a été tissée à Bruxelles,” Gazette des Beaux Arts 70 (1967): 253-278. She notes the former existence of an early sixteenth-century, six panel artwork described in a 1548 inventory that once belonged to Prince Erard de la Marck, Prince-Bishop of Liège, and was entitled Los Sentidos: it represented the five senses and included a sixth panel with the inscription liberum arbitrium. She interprets a mon seul desir in light of the Latin in Los Sentidos, suggesting that the Lady may use her senses according to her free will or only desire.

2. Consider, for example, the many legends of Robin Hood and Maid Marian, several contemporary in time with these tapestries, in which the virtues of a counter-cultural Christ (“stealing from the rich to give to the poor”) and an innocent Marian maid are represented in two life-like, noble characters. For discussion, see Stephen Knight, Reading Robin Hood: Content, Form, and Reception in the Outlaw Myth, Manchester Medieval Literature and Culture Series (Manchester University Press, 2015, repr. forthcoming 2017), esp. chap. 7, “The Making and Re-Making of Maid Marian.”

3. Carmen Decu Teodorescu, “La Tenture de la Dame à la Licorne: Nouvelle lecture des armoiries,” Bulletin Monumentalde la Société Française d’ Archéologie 168:4 (2010), 355-67.

4. “Cadency marks,” Heraldric Dictionary, University of Notre Dame. http://www.rarebooks.nd.edu/digital/heraldry/cadency.html. Accessed 28 March 2017.

5. “La Dame à la Licorne,” Wikipédia (française). https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/La_Dame_%C3%A0_la_licorne#Origine. Accessed 28 March 2017.

6. Kristina Gourlay, “La Dame à licorne: A Reinterpretation,” Gazette des Beaux-Arts 130 (Sept. 1997): 215-232.

7. Marie-Elisabeth Bruel, “La tapisserie de la Dame à la Licorne, une représentation des vertus allégoriques du Roman de la Rose de Guillaume de Lorris,” Gazette des Beaux-Arts(Dec. 2000): 215-232.

8. See Anne Davenport, “Is there a sixth sense in The Lady and the Unicorn Tapestries?” New Arcadia Review 4 (2010): http://omc.bc.edu/newarcadiacontent/isThereASixthSense_edited.html and Shelley Williams, “Text and Tapestry: The Lady and the Unicorn, Christine de Pizan and the Le Vistes” (Diss., Brigham Young University, 2009).

9. See, for example, Carl Nordenfalk, “The Five Senses in Late Medieval and Renaissance Art,” Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 48 (1985): 1-22, esp. 7-10.

Source:

Source:

Source:

Source:

My poems

My poems

My essay, “Tolkien, Eucatastrophe, and the Re-writing of Medieval Legend,” appears in Mallorn: The Journal of the Tolkien Society 58 (Winter 2017).

My essay, “Tolkien, Eucatastrophe, and the Re-writing of Medieval Legend,” appears in Mallorn: The Journal of the Tolkien Society 58 (Winter 2017).